One of the beautiful things about bookbinding is that many books, especially ones with simple structures, can be created with just a handful of materials. But before we jump straight into supplies, it can be helpful to first think about the purpose of the book you’re making. Will it hold writing, sketches, watercolor paintings, or memories? Is it something you’re making purely to learn and experiment, or is it a book you hope to gift or eventually sell? Your answers will ultimately guide your material choices.

In this post, I’ll be walking you through the first of eight basic material categories to help you build a thoughtful foundation for your bookmaking journey. To no one’s surprise, the first essential ingredient in bookbinding is paper. It comes in a variety of colors, textures, finishes, and weights, and can play many roles in a handmade book. Color, texture, and finish are fairly easy to understand, but paper weight tends to be a little more complex.

In the United States, paper weight is referred to in pounds (lbs), and terms like text weight, writing weight, cardstock, and cover weight often get used. Within the US system, a text weight paper and writing weight paper can ultimately share a similar thickness—which can understandably cause confusion. This topic alone could fill its own blog post, so to keep things simple here, I’ll be referring to paper weights in GSM, the international standard. GSM stands for grams per square meter and while there are always exceptions, a higher GSM number generally means a thicker, heavier paper and a lower GSM number generally means a thinner, lighter paper.

For bookmaking, I like to divide paper into these three main categories:

- Text Block

- Decorative

- Practical

1. Text Block Papers

Text block papers make up the core of your book. They’re the pages you’ll write on, sketch on, or print text and images onto. The ideal weight varies depending on your book’s purpose, but a good rule of thumb is to look for paper that is thin enough to fold cleanly without cracking at the spine, while still being thick and opaque enough to prevent distracting show-through.

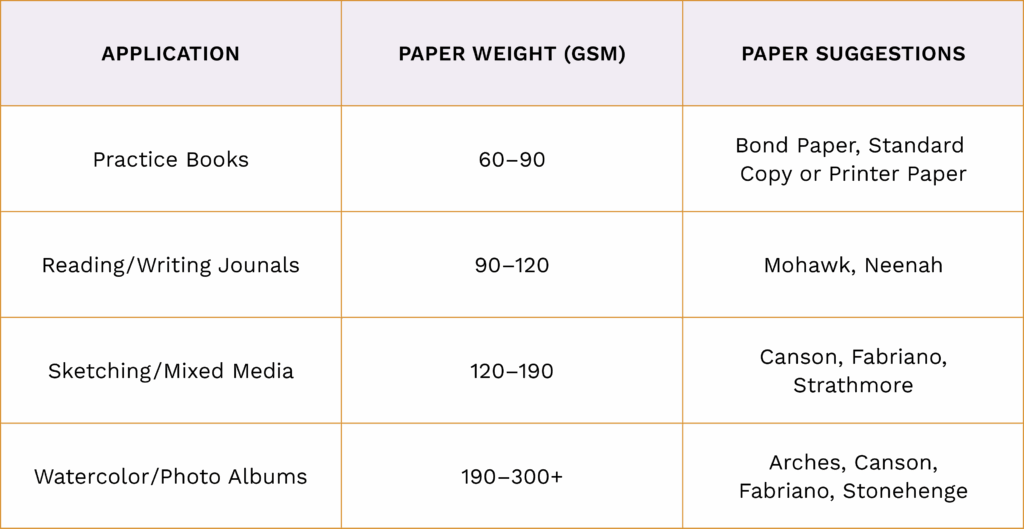

In the chart below, you’ll find suggested weight ranges and a few brands to explore based on how you plan to use your book. Nothing listed is meant to be absolute, simply a helpful starting point as you discover the materials that best suit your goals.

2. Decorative Papers

Whether handmade or mill-made, there are endless possibilities when it comes to decorative papers. In bookbinding, these papers can offer a solid flood of color, interesting textures, or be filled with richly patterned designs. Some can be pieced together in the form of a collage or even woven from scraps to create something entirely unique.

Decorative papers can be used in many ways: as soft covers, adhered to boards as part of a hard cover, inset panels on a case, or as endpapers and pastedowns inside the book. When choosing these materials, it’s helpful to consider both their aesthetic and function. Books are meant to be used and loved, so look for papers that balance beauty with durability, flexibility, and offer resistance scratches and fingerprints.

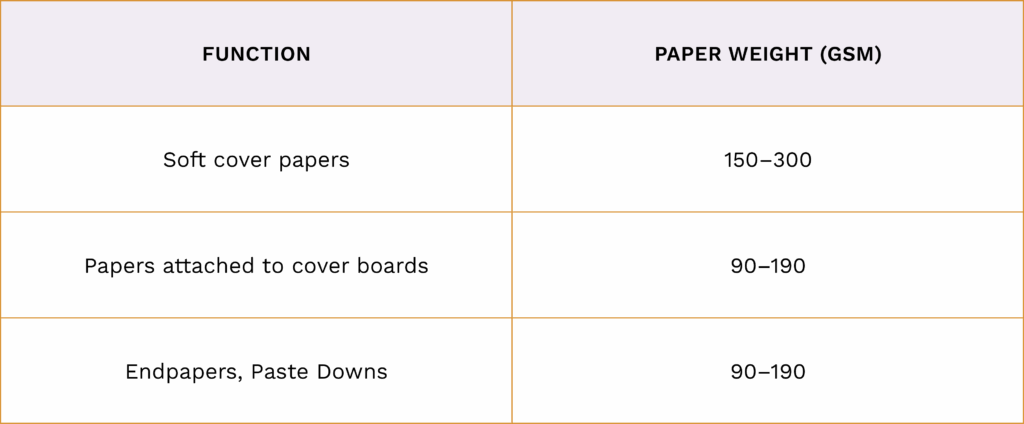

The charts below provide suggested weights for the various uses of decorative papers and a few paper varieties categorized by visual style.

3. Practical Papers

Alongside text block and decorative papers, bookbinding also relies on a few practical papers—materials that help with gluing, drying, and reinforcing structural components such as the spine.

• WASTE SHEETS

When undertaking any task that involves glue, using newsprint, blotter paper, or any inexpensive absorbent sheet can help prevent your working surface from becoming sticky and also be used to mask off areas you don’t want glue to seep into. I can personally attest that there’s little worse than being nearly finished with a book only to set it down on a hidden dollop of glue!

• MOISTURE BARRIERS

Moisture barriers usually come into play after glue-related steps, especially when the book or its components will be pressed under weight (such as wrapping covers in book cloth or casing in a text block). As the name suggests, their purpose is to prevent moisture or adhesive from transferring to other surfaces. Materials like wax paper, freezer paper (waxed on one side), or plastic sheets such as acetate work well as moisture-resistant barriers since they can be placed between pages or materials and removed easily once dry.

• SPINE LININGS

The spine is one of the hardest-working parts of a book, holding the sewn signatures and absorbing the stress of opening and closing. To reinforce it, binders often apply one or more lining layers made of strong tissue papers, cardstock, or other flexible but supportive materials. And while not technically a paper, mull (a loosely woven, cheesecloth-like fabric) is worth mentioning here too. Spine linings help add durability and longevity to a book, and in some cases, are used to create a smoother, more uniform surface along the spine.

A Few More Paper Tips to Keep in Mind

• GRAIN DIRECTION: THE GOLDEN RULE

One of the most important things to consider when choosing your materials is the direction of the grain. With the exception of handmade papers, most commercial papers have pulp fibers that run in a specific direction. In bookbinding, the grain of your paper (as well as your bookboard and bookcloth) should run parallel to the spine. This helps the paper fold cleanly and allows the pages to open and turn with ease. When materials are attached crossgrain, the paper can warp as the glue dries, and over time, humidity can also cause crossgrain materials to expand unevenly—making it harder for your book to stay flat.

• OPT FOR ACID-FREE

Have you ever noticed that some papers will naturally yellow and become brittle over time? This is due to a substance called lignin, a natural component of wood pulp that isn’t always removed during cheaper manufacturing processes. As lignin breaks down, it creates acids that cause paper to discolor and deteriorate. Acid-free papers are made by removing or neutralizing these acidic elements, resulting in sheets that remain much more stable as they age. When purchasing paper, look for labels like “acid-free,” “pH neutral,” or “archival” to help ensure your books have a long and happy shelf life.

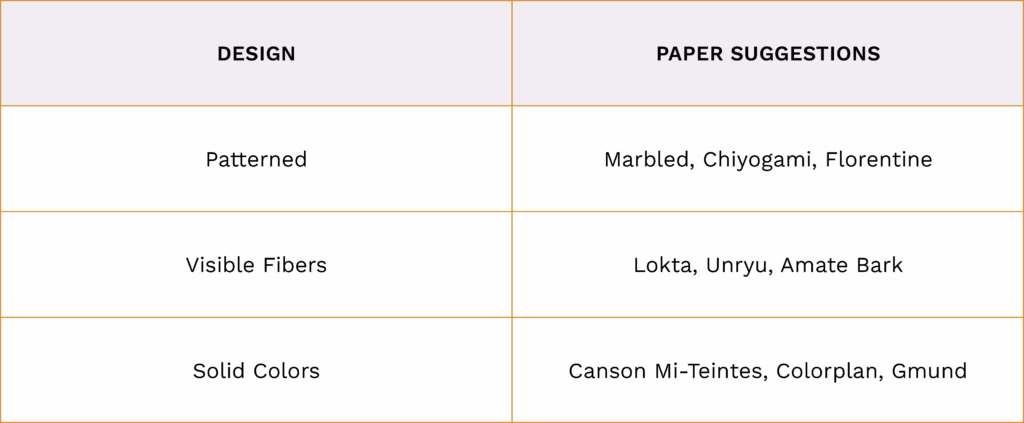

• PAPER SAMPLES & SWATCH BOOKS

While you can absolutely find paper at local office supply chains or stationery shops, many specialty sheets (and most bulk options) are only available online through mills or commercial suppliers. This usually means choosing materials based solely on a digital image which is never ideal. When possible, I highly recommend ordering individual samples or swatch books so you can see the true color in real light, feel the texture, and understand the weight before committing. It’s a lot like bringing home paint swatches—what looks perfect under store lighting can feel completely different once you’re actually working with it in your space. Swatch books have saved me so much time and money by preventing those surprise orders where the material ends up nothing like what I expected.

I hope this overview offers a helpful starting point for discovering the papers that suit your style and the kinds of books you dream of making. In the next post of this series, I’ll be covering another widely used material in bookbinding, Book Board (also known as Binder’s Board). We’ll take a look at the different types available and how to choose the right one for your projects.

As always, thank you for reading along!

Until next time,

–Allyx